Cabo Ligado Monthly: December 2020

December at a Glance

Vital Stats

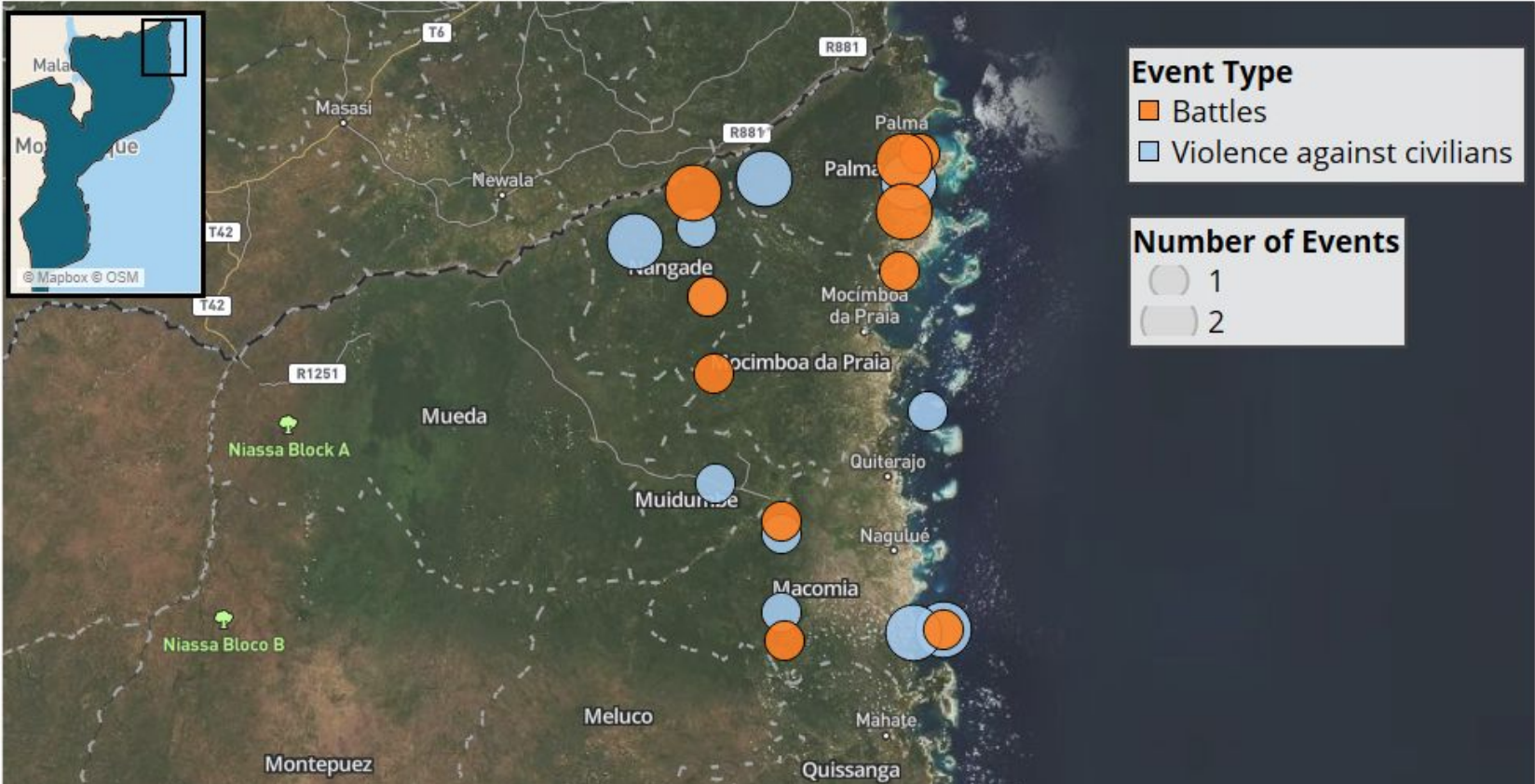

ACLED recorded 35 organized political violence events in December, resulting in 93 fatalities

Nearly a third of the deaths were the result of a government attempt to retake Awasse, Mocimboa da Praia district on 15 December -- 24 insurgents and six government troops lost their lives in the resulting battle, but the town remained in insurgent hands

Other events took place in Ibo, Macomia, Metuge, Muidumbe, Nangade, and Palma districts

Vital Trends

Civilian fatalities were down sharply after the November massacres in Muidumbe district, due in part to the rainy season reducing both insurgent and government operational capacity

Both the southern and western roads out of Palma were hotly contested in December, with 26 incidents and 38 fatalities in Palma and Nangade districts

International aid agencies serving displaced people in Cabo Delgado announced that they lack funding to provide necessities to vulnerable populations for the whole of 2021

In This Report

Discussion of low probability/high impact events that may shape the conflict in 2021

Analysis of the Northern Integrated Development Agency and the record of its de facto head, Celso Correia

The latest on Mozambique’s negotiations to secure external support for its counterinsurgency effort

December Situation Summary

Fighting in Cabo Delgado died down somewhat in December as heavy rain made travel more difficult and insurgent attacks focused more on resource gathering than on achieving long term strategic objectives. Yet threats to civilians and the Mozambican government’s counterinsurgency effort persisted; these were exacerbated by budgetary constraints.

In early December, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) released a report detailing its funding needs for Cabo Delgado in 2021. The $254.4 million funding request reflects the rapidly expanding humanitarian crisis in northern Mozambique -- OCHA had only asked for $35.5 million for its 2020 Cabo Delgado operations. The new request was a warning, both about the scale of misery in Cabo Delgado and about the international community’s willingness to provide the money necessary to keep vulnerable people fed and sheltered. OCHA’s 2020 request, roughly 15% the size of this year’s, was never fully funded by the international community. The chances for anything like full funding for the $254.4 million request seem quite low. Indeed, by January, the World Food Programme’s budget request for Cabo Delgado was only 18% funded.

Within the Mozambican government, competition for resources between the police and military increased in December. A report emerged that the military had secured a contract with South African weapons makers Paramount Group. The contract is said to involve the sale of armored vehicles -- some of which have already been spotted in Mozambique -- and helicopters, as well as training for Mozambican troops. In addition to the added capabilities the contract could bring to government forces overall, the contract is notable because it seems to replicate for the military what the police have in their contract with Dyck Advisory Group. To the extent that the contract is an effort to empower the military relative to the police rather than to find the most efficient way to augment government capacity, it shows how far the government still has to go to find a coherent counterinsurgency strategy.

In the conflict zone itself, the biggest event in December was the reversal of a government attempt to retake Awasse, Mocimboa da Praia district on 15 December. Awasse sits on the road from Mueda to Mocimboa da Praia. Controlling it is a crucial step in any attempt to retake Mocimboa da Praia with forces from Mueda. Insurgents ambushed government troops attempting to retake the town on the 15th. The ensuing battle resulted in significant casualties on both sides. Government forces eventually withdrew; no attempts on the town have been reported since.

Outlier Events in 2021

In recent months, three low-probability events have become frequent conversation topics among Cabo Delgado watchers: geographic expansion of insurgent base areas; possible insurgent attacks in Pemba or Mueda; and a potential embrace by the Mozambican government of direct foreign military intervention. Each of these would dramatically shift the character of the conflict if they were to happen. While none of them are likely in the near term, they are all well within the realm of possibility. This month, we will look at each one of these potential events in turn, and discuss both the likelihood and implications of them taking place.

The first potential outlier event is insurgents expanding their areas of long-term occupation west into Niassa province. Concern about Niassa among analysts picked up in 2020. The economist João Mosca, director of Mozambique’s Rural Environment Observatory, said in a recent interview that insurgents facing mounting counter offensives in Cabo Delgado could push into Niassa to find areas to live further away from government forces. Mosca also noted Niassa suffers from the same elevated poverty levels and extreme inequality that exist in Cabo Delgado, potentially making Niassa a fertile recruiting ground for the insurgency. Indeed, in December, Mozambican Prime Minister Carlos Agostinho do Rosario specifically urged displaced people living in Niassa to resist insurgent recruitment, demonstrating that the government itself is concerned about Niassa being dragged into the conflict.

Durable insurgent expansion into Niassa would put heavy strain on the already overstretched Mozambican security services, but is unlikely to take place. Security force logistical capabilities and the government’s willingness to arm local militias both increase as you move west across Cabo Delgado, which makes sudden westward expansion difficult for the insurgency. In addition, the scenario Mosca outlined of insurgents being forced to seek new sanctuaries after being pushed out of their existing base areas has not come to pass. Instead, insurgents remain well ensconced in Mocimboa da Praia district, and still move with impunity in large parts of western Palma and eastern Macomia districts. As long as those remain safe havens, insurgent expansion aims are likely to remain limited and gradual. Even the insurgency’s push into Tanzania in October now seems to have been less about pursuing new territory and more about capitalizing on the occasion of the Tanzanian election.

The second potential outlier event is insurgent attacks on government strongholds in Pemba or Mueda. This is distinct from the first outlier event because rather than being occupations, any attacks on Pemba or Mueda in the near term are likely to be one-off incidents intended to sow fear and destabilize local governance. Multiple reports emerged in December alone of suspected insurgents being arrested in Pemba, suggesting that the likelihood of an existing insurgent network there that might be able to facilitate attacks is quite high. In November, insurgents were operating so close to Mueda that many civilians fled, fearing that insurgents would infiltrate or even overrun the town despite a robust military presence and local militias armed with the newest small arms the government had to offer. It is not at all clear, however, that the insurgents had any intention of carrying out what would have been a high-cost attack on Mueda. Instead, the insurgents were able to generate enough panic to cause many refugees to flee to Montepuez without having to overextend their fighters.

One-off attacks in Pemba or Mueda are significantly more likely than insurgent westward territorial expansion, but the effect of such attacks would also be much less significant. These attacks would grab headlines, but would be unlikely to alter the fundamental dynamics of the conflict. Arguably, they would actually represent a step down in ambition on the insurgents’ part, since most insurgent operations to this point have been building toward creating areas of territorial control, which would be difficult to accomplish or maintain in Pemba or Mueda. In any case, they are unlikely in that they would require a major shift in the insurgents’ modus operandi.

Finally, there has been a great deal of speculation that the Mozambican government will become more open to the idea of direct foreign military intervention in Cabo Delgado in 2021. French Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly recently went as far as to list French military units that could be deployed to Cabo Delgado. To this point, the Nyusi administration has erred heavily on the side of protecting Mozambique’s sovereignty from any foreign militaries that would take their orders from their home countries, rather than Maputo. Yet, if President Nyusi reversed himself, there would likely be a range of offers that could provide added manpower, air assets, and intelligence capabilities badly needed by Mozambican security forces.

The cost of doing so, however, would likely be steep. Escalation on the part of the international community -- especially from France or the United States (US) -- would likely be met with escalation on the part of the Islamic State (IS). The more the conflict becomes internationalized, with foreign militaries making more decisions on the government side and IS central making more decisions on the insurgent side, the less prospect Nyusi has of being able to end the conflict through eventual political negotiation. Bringing in direct foreign military assistance would change the character of the conflict on the ground, but it would also change the politics of the conflict in an uncomfortable way for the Mozambican government by taking a certain amount of decision making power away from Maputo. Barring a change in the conditions on the ground, it is unlikely that Maputo will embrace that discomfort.

Celso Correia and ADIN

When Mozambique’s Northern Integrated Development Agency (ADIN) was formally unveiled in a ceremony in Pemba in late August 2020, Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Africa Program senior associate Emilia Columbo told Cabo Ligado that the agency’s success depended on its programs being “quickly and transparently executed.” By the time the unveiling ceremony was over, the agency’s transparency was already in doubt. ADIN’s ostensible head, Frelimo stalwart Armando Panguene, made a brief speech at the event and then ceded the floor to Agriculture Minister Celso Correia. Correia then gave a long and detailed briefing on his plans for the agency, making it very clear that he was in charge despite Panguene’s title.

Correia’s presence at the unveiling was no surprise -- ADIN had been placed under the Agriculture Ministry months earlier. What was notable was the granularity of Correia’s involvement. Correia made clear in his presentation that he would be making the decisions about how ADIN’s eye-popping budget -- $763.6 million in international pledges and domestic funding -- would be spent. Given the role ADIN was meant to play in the government’s counterinsurgency effort as the lead agency for both humanitarian relief and development projects to improve social cohesion, that made Correia a key figure in determining the government’s conflict strategy.

That level of control has drawn concern from civil society organizations. The Center for Democracy and Development (CDD) has led the charge against Correia, pointing out that he already administers another development fund -- the National Fund for Sustainable Development -- which, CDD alleges, he has used to fund politically advantageous projects outside the scope of his responsibilities. Correia was also in charge of Frelimo’s campaign in the 2019 national elections. He did his job arguably too well. President Nyusi won re-election overwhelmingly, but the campaign was marred by fraud and violence. In Cabo Delgado in particular, the government registered about 9,000 more voters than it projected to be in the entire province’s electorate despite the ongoing conflict, a claim that beggars belief.

Whatever questions Correia’s past appointments raise about his commitment to transparency, they demonstrate clearly the faith that Nyusi has in him. Correia has consistently been one of Nyusi’s point men on development programs that require coordination between Mozambican domestic politics and international donor relations. Overcoming that coordination challenge is arguably ADIN’s core task, given both the amount of international money involved and the high stakes of development projects meant to address -- and, in the eyes of some, resolve -- a conflict that has already killed thousands and shows no sign of abating. One rumor suggested that Correia intends to signal his commitment to the task by moving his office to Pemba and running a “war cabinet” from the north. A well-connected source in Maputo had not heard of any such plan, and a source in the Pemba business community was surprised to hear the speculation, saying he had not seen Correia in Pemba in some time. Even if the rumor is untrue, however, the fact that it circulated in the first place highlights Correia’s centrality in both government and donor plans.

Yet, like the Pemba businessman, vulnerable people in Cabo Delgado have not seen much of Correia. For all the concerns about transparency, where ADIN has really failed so far is the speed at which projects have moved. Correia promised at the unveiling event in August that ADIN would take over humanitarian aid distribution in Cabo Delgado, but there are no indications that it has done so. A source on the ground in Cabo Delgado, when asked about ADIN’s presence in the province, questioned whether the agency still existed. He had seen no indication that they were involved in humanitarian operations at all. Indeed, as of December, the agency still had no strategic plan for beginning its involvement in humanitarian operations.

That may be a function of lack of funds. At the agency’s launch, the vast majority of its projected budget had not been transferred from donors. The $19 million in its coffers was project funding, arriving pre-earmarked for development projects in agriculture, health, and water supply issues. Since then, the government has declined to appropriate any domestic funds to ADIN, saying that international donors will cover the costs. Yet, with even the World Food Programme, which is already conducting vital humanitarian work in Cabo Delgado, struggling to raise funds in an era of COVID-19-driven aid austerity, ADIN may need to wait longer to realize its funding goals.

Whatever the reason, it is clear that the grand plan of addressing underlying social and economic issues in Cabo Delgado by pairing international donor funds with a figure as politically able as Correia is not substantially closer to fruition than it was last August. As time drags on and promises remain unfulfilled, ADIN could end up hurting the government’s relationship with Cabo Delgado civilians rather than fixing it.

International Support Update

An overall image of delay, prevarication, uncertainty, and a lack of urgency continues to characterize Mozambique’s approach to securing international support for its efforts to tackle the insurgency in Cabo Delgado. Maputo is intent on retaining overall control. Despite reaching out to multilateral bodies, sovereignty politics lends itself to a preference for bilateral options over which Maputo feels it can exercise more control.

Developments in December brought no further clarity on how Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states might support Mozambique in Cabo Delgado. Southern African leaders were reportedly irritated by Maputo’s failure to bring more than a shopping list of needs to SADC’s extraordinary Organ for Politic is Defence and Security Troika meeting in Gaborone in late November. It has been promising to bring a plan of action to the table since May, but has still not done so. At the same time, Mozambique insists it neither wants, nor needs, “boots on the ground” from its neighbors or elsewhere. It also reportedly does not trust Botswana (currently chairing the Organ Troika) or Tanzania to be part of any collective intervention. At the heart of Maputo’s prevarications remains the ongoing challenge of putting in place a coherent security strategy with solid backing from the entirety of government and Frelimo.

This further delay in progress prompted a push from Organ Troika leaders (Botswana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa) to meet in Maputo on 14 December at a “high level consultation” hosted by Nyusi, and attended by Tanzania’s vice president, Samia Sulihu. The Mozambican president resisted further calls for discussion on a possible collective regional intervention and a decision on SADC intervention or assistance was pushed back to a dedicated summit on Cabo Delgado scheduled for 17 January (and since postponed, ostensibly due to the surge of COVID-19 in the region).

Zimbabwe continues to push a narrative for intervention. In mid-December, president Mnangagwa’s spokesman, George Charamba, suggested the regional body was “edging closer” to deploying troops. Several sources claim Zimbabwe already has had a team of at least thirty advisors in Cabo Delgado for much of 2020. Botswana’s Foreign Minister, Dr. Lemogang Kwape, however, maintained SADC had not made any decision on a prospective military intervention.

Portugal has taken the lead in trying to define the shape of European Union (EU) assistance in Cabo Delgado. Portugal’s Defence Minister, Joao Gomes Cravinho, was in Maputo from 9 to 11 December to boost bilateral defence cooperation; this includes a resuscitation of training for Mozambique’s marines, special forces, and tactical air control. The meeting communique added that “areas of specific interest, such as cyber Defence, cartography, hydrography and industrial defence cooperation were signalled, with the Ministers mandating technical teams to further develop the respective implementation modalities.” This builds on a 2018 bilateral defense agreement for Portugal to provide technical and equipment support. The training is expected to include components from the police (PRM) specialized units.

Ahead of his visit, Cravinho suggested Portugal would consider sending troops to Mozambique if requested either bilaterally or within an EU framework. Under the current circumstances, this is highly unlikely as the EU has ruled out troop deployment as a type of support it is considering. A military team from Lisbon is expected in Maputo in early January to work with Mozambique’s security forces to design a support program. A rapid resuscitation of Portugal’s training programs, however, must be tied to a broader strategy of reconfiguring security options, at the same time strengthening current counterinsurgency efforts.

Portugal assumed the presidency of the European Union on 1 January 2021 and is expected to use its position to push options for EU assistance. Despite an in-principle agreement with Mozambique in October 2020 to explore options for EU support, and a number of meetings that have circled around these issues, tangible progress towards some hard agreement is elusive.

On 15 December, Josep Borrell Fontelles, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, told the European Parliament, "We are waiting for the green light from Mozambique to send out a security experts’ mission who have been appointed since November and who are ready to leave. We are just waiting for authorization." Borrell hinted that there was some confusion from Maputo. It appeared unclear whether the Nyusi government really wanted to engage the EU or to only engage bilaterally with certain EU member states. The latter, however, are unlikely to operate in isolation from the collective.

EU officials have cautioned against an approach that privileges security and sidesteps addressing causal factors of the conflict, countering violent extremism, and development. An EU fact-finding mission to Cabo Delgado is an obvious move to help inform Brussels of the situation on the ground, but Maputo has not put this option on the table. Borrell has complained that EU officials in the country face restrictions on their movement. As such, Mozambique’s penchant for constraining bureaucratic regulation continues to frustrate on several fronts, such as the fast tracking of visas for international humanitarian staff.

The EU is unlikely to respond positively to Maputo’s ‘shopping list’ approach, unless it is clear how the resources requested tie into a focused hard security strategy and a wider angle human security strategy. Maputo must appreciate that EU support will necessitate a degree of accountability to EU taxpayers, and must accommodate this if it is to benefit from the largesse of Brussels.

The US has also moved toward making more concrete offers of support. During an early December visit to Mozambique and South Africa, the US coordinator for counterterrorism Nathan Sales (representing the State Department) announced on 8 December that Washington was “seriously interested” in a partnership with Mozambique to “contain, degrade and defeat” armed groups in Cabo Delgado province, “strengthening our friendship while together we face the challenge of terrorism.” Specific mention was made of potential support for building civilian law enforcement and border security challenges. As with others offering support to Maputo, Sales argued that support must go beyond a security lens, but did not provide any detail on what a plan might include (content wise or in terms of financing), or reflect on ‘lessons learnt’ from the over 20 years experience the US has fighting extremism on the continent.

The US also pointed to an overlap between the drug traffickers and extremists and the types of conditions that enable them to thrive. They have offered to support the Mozambican government’s counter-narcotics efforts in order to cut-off what it believes is a financial lifeline for the insurgents operating in Cabo Delgado. This raises questions about the import and efficacy of existing (albeit nascent) efforts to forge a UN backed trilateral anti-narcotics strategy between Mozambique, Tanzania, and South Africa.

US counter-terrorism support to Mozambique to date has been limited. Structural shifts in the US-Mozambique counter-terrorism relations during the Trump administration, such as Mozambique’s admission into the Partnership for Regional East African Counterterrorism, have not resulted in major funding increases. USAID currently supports several research and countering violent extremism projects relating to the conflict.